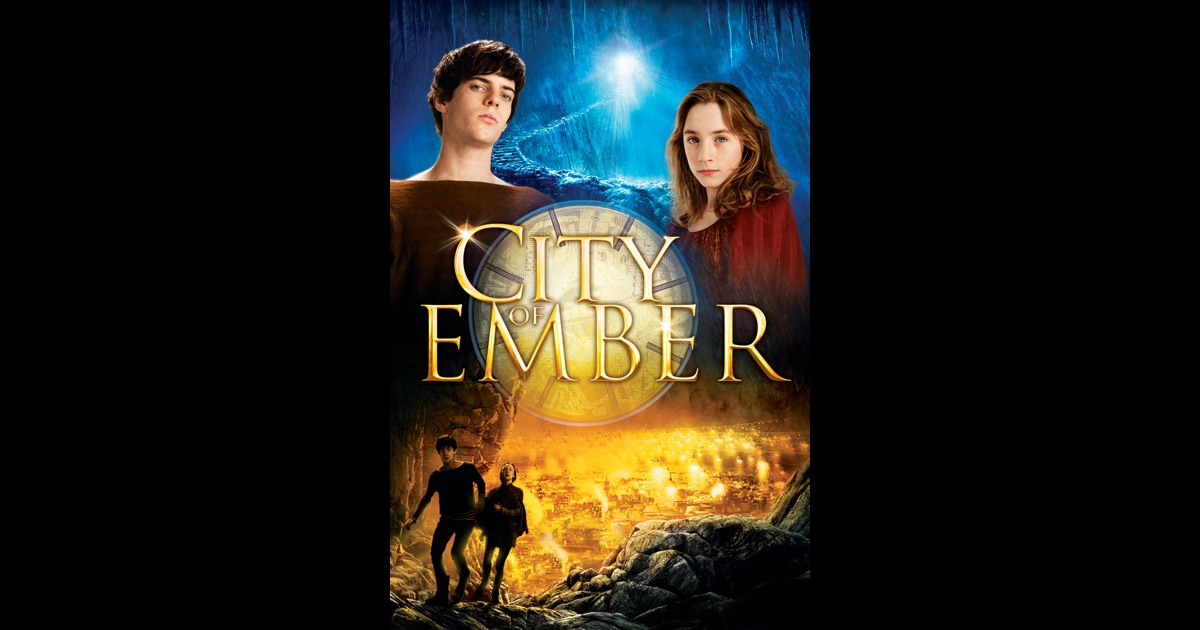

CITY OF EMBER RATED FULL

Forster’s infinitely more evocative 1909 story, “The Machine Stops.”īut not to worry: the boundless resourcefulness of two curious, clean-cut adolescents full of gee-whiz enthusiasm may lead humanity back into the fresh air and sunlight. Ember recalls the more sophisticated world of E. Because the people of Ember, forbidden to venture into the above-ground world, have forgotten their past, they face subterranean extinction. Ominous blackouts regularly plunge the city into darkness and supplies are depleted.

CITY OF EMBER RATED HOW TO

Now it is breaking down and no one knows how to repair it. For 250 years Ember has been run by a generator. The movie’s overriding message is anti-technological boilerplate. Tim Robbins is also on hand as Doon’s earnest, secretly rebellious father, who spends his days tinkering with exotic inventions.

Murray looks too bored to convey more than token menace.

CITY OF EMBER RATED MOVIE

Bill Murray droops through the movie as the fat, corrupt mayor of Ember, who maintains a secret bunker stocked with the canned goods that have become scarce. “City of Ember” tosses in an unscary monster that suggests a giant, riled-up rooster on speed, as well as harmless, oversize creatures resembling beetles and cockroaches. Because telephones no longer work in Ember, the machine is a quaint relic from another age. The wittiest is a primitive telephone-answering machine that resembles the do-it-yourself hi-fi kits assembled by audiophiles in the early days of stereo. The best things about this yarn are scenes of ominous grinding machinery of the kind found in railway yards, as well as several zany gadgets worthy of Rube Goldberg. This decrepit hole in the ground, from which there is no easy exit, is where humanity huddles in mounting discomfort under the autocratic rule of a series of mayors who dress like budget-conscious impersonators of Henry VIII. In Hollywood-speak, it has a weak second act.Īside from its generic adventure music, the predominant noises are the clanks, squeaks and hisses of rusted machinery and steam pipes in the crumbling, labyrinthine underground city of Ember. At only 95 minutes, the movie feels as though it had been shredded in the editing room. Most of the time, however, it’s a whiz-bang kid’s film with neat gadgets and sound effects and an extended chase and escape sequence through underground rivers and tunnels. In Jeanne DuPrau’s children’s novel (the first of the four-part “Book of Ember” series), from which the film was adapted, Lina and Doon are dewy 12-year-old adventurers loaded with pluck but devoid of personality.Īt moments “City of Ember,” directed by the British filmmaker Gil Kenan (“Monster House”), suggests a mild satire of end-of-days ideology, especially when Mary Kay Place appears as a prating, singsongy proselytizer for the status quo. Ronan, who is 14, and the dimple-chinned 24-year-old heartthrob Harry Treadaway portray Lina and Doon, best pals fleeing a subterranean dystopia guided by the kind of cryptic instructions found in the “National Treasure” movies.

In “City of Ember,” she has nothing to work with.

To watch the talents of Saoirse Ronan, the brilliant young actress from “Atonement,” being wasted in the science-fiction juvenilia of “City of Ember” is to be reminded that a powerful performance needs an equivalent screenplay.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)